Romano Felmang: An Italian for Comic Books Translated from the Italian magazine Fumetto by Bob Griffin

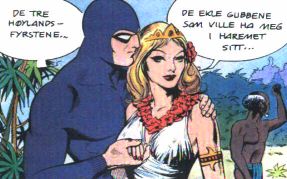

("The Wedding Gifts", Fantomet Nr.18 1995)

("The Wedding Gifts", Fantomet Nr.18 1995)

Introduction by the Editors:

The 60s saw the flourishing of a sea of new creators of comics, accompanying first the phenomenon of the black comic-strips and then of the erotic.Hidden behind very strange pseudonyms, many of them have remained unknown to the majority of fans. While fans and the new criticism (la critica novella) sought out the creators of the pre-war period and exerted themselves in discoveries related to the hot years of the post-war period, from that sea of initiatives which saw light in the 60s, few authors emerged: Magnus, Zaniboni--discovered more for his real merits than for his past--Max Bunker, Angiolini, Frollo, Romanini, Marraffa, Verola, Barbieri...

But, for the few who have succeeded in riding the wave, many remained underwater without gaining critical attention. This happened not because of a lack of merit or because the comic-strips on which they worked were without interest, but only because the generation gap between those who wrote about what had happened in the comics' distant past and those who devoted themselves exclusively to speaking energetically about the present (without any historical memory), had produced a profound break, a kind of tragic rupture, in which many, many names of national comic-strips had disappeared.

Here we are attempting to achieve at least a partial recovery of those authors - critically speaking - giving them the faculty of speech, in an attempt to reconstruct the forgotten faces of the 60s and 70s.

Interview with Romano Felmang

D: How did your interest in comic-strips begin?R: I have always been a fan of comic-strips; when I was a child there was no television and, as a pastime, my generation read mountains of comics. They were my favorite textbooks in the period of elementary and early middle school. I started by regularly acquiring Tony Boy; I really like his format on the vertical line, like a filmstrip; then there followed The Little Sheriff, Sciuscia, Forza John, Nat del Santa Cruz, Captain Miki, The Intrepid, etc. I stopped reading comics when I was about 15, but began again when I was about 20. I tried to recover all that I had lost during the years of my "estrangement" by way of the back-issue service and the used comic stands.

D: How and when did the idea occur to you to draw them?

R: From childhood my favorite pastime was drawing. I created comic stories on my school notebooks and believed that as a grown-up I would continue to like creating comics. I seriously began to consider this as a possible career when I was older. One morning, at the beginning of 1964, I noticed at the newsstand a copy of Mandrake, "A Lost World" (Il Vascello, #51), I bought it and saw that Fratelli Spada Publications were produced in Rome. It was one of those rare cases of a Roman publisher. I had thought that comic publishers always were in Milan.

I considered the possibility of pursuing a cartoonist's career the that moment when I lost interest in a teaching career. The next day, after telephoning, I went to via Enea 77, offices of the Fratelli Spada press, and I presented myself as an illustrator of comics with zero experience. A young woman addressed me, very kindly, and gave me a two issues of The Phantom from the American Adventures Series - "The Island of the Dogs" (L'isola dei cani) - saying: "These are recent stories of the Phantom from the United States; the production is syndicated, but it's not enough to cover our weekly requirement. For this we need illustrators who imitate Sy Barry, the leading artist of the American comic-strips. Make us a couple of trial panels in this style!"

Those two issues were beautiful and deeply captured my imagination. During the following days I tried several times to draw The Phantom of Sy Barry, but the results were very poor. I could not confront such a demanding character tout de suite and succeed in imitating an artist, whom I considered the best at that time. So I had to practice and wait for a later opportunity. But I was sure of one thing: I liked the work and I was firmly committed to doing it.

My new opportunity came a few months later: thrillers appeared in strips, the so-called "blacks" or "pocket" strips, and with them new publishers were looking for new illustrators, since the artists of the preceding generation were already employed. Among the classified of the biggest daily of the capital there appeared some ads: the publishers Cofedit were looking for illustrators of comic-strips. About a hundred aspiring young illustrators showed up at the offices of the publisher, but only two were chosen: myself for Fantax and another assigned to the new character, Demoniak.

I illustrated a couple of episodes of Fantax and immediately after left for military service. During the period of Sten al Car di Pistoia I again had work, contributing to the magazine Colt 45 published in Florence by Vallechi.

In the fall of '66 the times were now ripe and I created my first real professional story for The Phantom, "The Robbers of the Tomb of the Great King" (I Ladri della tomba del Gran Re) which was published in the Classics of Adventure Series in Italy and France. The following year I also began to work for the publishers at Milan: Johnny Beat for Cervinia, Kriminal for Corno, The Intrepid comics for Universo. My involvement with this last group lasted until the beginning of the 80s. My team and I produced many special issues published in the course of the years in various magazines of that publisher: The Rascal, The Intrepid and The Bliz comics.

D: Tell me about your team: When and how did the cartoon studio begin with an American system of work?

R: During a trip to the U.S.A., a friend of mine had met Wallace Wood at that time working on Dynamo of the Thunder Squad and with Witzend. He told me how the work of the great Wally and his various assistants was organized.

Since the 50s I had been an admirer of the EsseGesse; at that time I didn't know who hid behind this symbol, but it was a group who managed to produce two issues a week, Miki and Blek, and the quality was good.

At any rate, I became curious about the production unit, so between '67 and '68 there was born what I called then the "Cartoonstudio."D: Who were your first partners?

R: At first I worked together with other professionals of my generation; later on (1970-71), I gave in to the appeals of young men who were interested in making comic-strips and I gathered them enthusiastically into my studio.

D: Did you screen them to assure the attitude of the student-collaborators who would work with you?

R: My studio was always open to all, although I chose my students cautiously. There were many; some remained by my side just a few months, others many years; some still work with me.

D: Did you discover any new talent?

R: Yes, I had occasion to do so several times. The aspiring illustrators arrived completely lacking the necessary techniques without the faintest idea of how to create a comic-strip album. (Otherwise they would have directly approached a publisher, right?) But when they left my studio they had already reached a high level of preparation and professionalism.

D: Was there any resemblance between the "Cartoonstudio" and the current comic-strip schools?

R: Mine was a school where one learned to illustrate comic-strips in the practical manner, and I believe it is the best way. All attended the school, I have to say GRATIS, or rather I was the one who paid for their neophyte and elementary early contributions.

D: What were your chief comic-strip productions?

R: My studio work produced many "libere" (free-lance) stories, other than for Universe, and for Eura (Lance Story, Scorpio); I did this for fifteen years.

D: Moving on, having seen that today the Japanese "manga" (a type of Japanese art form which has it's roots in Ukiyo-e wood prints and other traditional art) are popular, were you not a precursor in this narrative arena?

R: At the beginning of the 80s there was a boom in animated Japanese cartoons on television. There were born then some of the publications for children which presented again in comic-strips the adventures of the main characters of those cartoons (TV Junior, Cartoons on TV, Noi Super eroi, etc.). Under the usual system of work, coordinated by a strong team, we created many episodes of a great number of Japanese characters. In this case my strips were more "Japanese" than those created by others, because to sketch the pencil illustrations there was a Japanese artist with ten years service in the studio of Osama Tezuka. Probably the young readers of that time now belong to the great host of fans of the original.

D: Do you still have a studio with some students?

R: In 1980 I started a family, and I no longer had time to follow new aspiring illustrators. Today I advise those who come to me as students or assistants to attend a cartoonists' school. Keep in mind that my chief activity has been teaching and that I have always done comic-strips as a hobby; so, I have preferred to dedicate my free time to my children rather than to those who wish to embark on the world of comics.

D: So, at this point, it's natural to ask you what you think of the schools that teach the making of comic-strips.

R: I don't have a well-defined position about the comic-strip schools, I know little about them. Just once, a few years ago, I was invited as a guest to a comic-strip lab and discovered that the students learned to illustrate comic-strips by MY method and that the "guest stars" of the course were very often my ex-student/assistants. Another school of the same time was teaching how to construct an episcope (opaque projector), identical to the one I had planned and built many years before. At any rate, I think that it's right that those who want to learn a profession pay to learn it.

D: Tell me about your daily work.

R: In 1986 I had the good fortune of knowing the person authorized by King Feature Syndicate to produce The Phantom stories for comic books. While we were talking about a serial conceived by me, Moon and Luan, the conversation ended with The Phantom and I said that I had already illustrated it many years before. I was asked then if I would like to collaborate in the production of these new stories and I accepted enthusiastically.

Since then I have been working on The Phantom which is published successfully in almost all the world (Northern Europe, Australia, England, the U.S.A., Brazil, etc.). It requires a certain high level of quality, and I take a lot of time to complete a story.

D: Do you have assistants for this work today?

R: I began alone, because my assistants at that time did not know the character and were not able to hit it off at the first shot, then I followed my normal organizational pattern. When I was asked to produce more, I thought of my friend Ferri, and convinced him to return to his favorite character. Since 1990 he has been the one who inks in his very elegant and polished style the greater share of the Phantom panels which I produce.

Otherwise, when I find myself far behind in my work, I sometimes get help from other friends, illustrators of proven ability.R: What is your method of working for The Phantom?

D: I have never had a well-defined method of working. When I'm not the one doing the translation, I carefully examine the arrangement of scenes, then I spend a few days researching references for the execution of the art work. My archives are well-supplied, but sometimes they are not inadequate. So I prepare a first layout with pagination, scene by scene, of all the panels that make up an episode. In the creation of the pencil illustrations, I don't embark from page 1. Since I already have the whole scheme for what I have to do, page for page, I begin with the so-called standard panels, that is, the easiest, and I put off until later the more demanding ones. I work at the drafting table and as soon as a dozen panels are done, I begin to ink them, or rather I pass them along to the great Ferri who really inks them. For the inking we use a "soft" pen (Brandauer or sometimes Sommerville) and we fill in with markers.

D: Tell me a little about the legendary Ferri.

R: Ferri was absolutely the finest among the Italian illustrators who became attached to the stories of The Phantom produced by Fratelli Spada Editions during the 60s. In many episodes he surpassed even Sy Barry himself! I have been, and still am, his fan; it's also thanks to his efforts, as in Le anime di pietra (The stone souls), that my desire for this profession and for the character of The Phantom has grown. But to learn more, I suggest an interview with him in one of the next issues of Fumetto.

D: Presently, you are the only Italian artist involved in a comic book series distributed in the States. Tell me about it.

R: The new series The Phantom, published by Wolf Publishing and distributed in England and the U.S.A. is having a respectable success, despite the enormous crowding of this current market, often inflated by non-commercial (and worse) products. The issues are well printed and have a high level of graphics and editing. I wish the Anglo-American edition the same success this character has won in Australia and Northern Europe where it is the best-selling series. I want to mention further that The Phantom draws on contributions from very professional artists and scenarists, coming from various countries: an international team for an international series!

D: Do you apply yourself only to The Phantom, or do you do other things as well?

R: Between me and my publisher there has developed a rapport of mutual esteem beyond one of friendship, on account of which I would never take time off from The Phantom to do other jobs. When new proposals come to me I refuse, in most cases.

D: Do you have other pleasures or interests besides comic-strips?

R: I enjoy American popular music of the period 1954-1960; my collection includes about 6,000 LPs and more than 2,000 CDs (rapidly expanding). In this regard I am more fortunate than other collector/friends, because, thanks to the kind of work I do, I can spend many hours a day immersed in my Dolby-surround system listening to my favorite music!

Biographical Sketch

Index of Felmang's Phantom Stories

- Romano Felmang was born in 1941 in the Roman quarter of Parioli. After graduating from high school, he continued his studies while entering the work world as a technical illustrator.

- His first experiences in the field of comic-strips were in 1964.

- After graduation from the Higher Institute of Physical Education and finishing military service, he divided his time between teaching and the profession of cartoonist.

- In 1968, more interested in commercial productions than in artistic masterpieces, he created the "Cartoonstudio", the hotbed of the new generation of Roman comic-strip creators. He collaborated with many Italian publishers producing hundreds of panels, both for established characters as well as for independent stories of all kinds.

- Toward the middle of the 80s, when Italian comics were at a crisis, he began to deal regularly with the foreign market. In 1986 he began working with the classic character of King Features Syndicate, The Phantom, and this occupies almost entirely his work-week. His artistic work reflects his admiration for this character.

© 1996 KING FEATURES SYNDICATE, INC. THE HEARST CORPORATION

© 1996 KING FEATURES SYNDICATE, INC. THE HEARST CORPORATION